Disarmament and Development,1982 June, Mrs. Catley-Carlson, UNICEF Dep EXD.

Filed under Moments peace - story collection | Thoughts from the UN community.In June 1982 the meditation group held three programmes on the occasion of the United Nations Second Special Session on Disarmament. The first was a meditation in the Dag Hammarskjold Auditorium on 7 June, the opening day of the Session, where delegates and staff joined to pray and meditate for the success of the Session.

On 21 June the group hosted a concert and luncheon at Headquarters, with guest speaker Mrs. Margaret Y. Catley-Carlson, Deputy Executive Director, (Operations) of the United Nations Children’s Fund, launching the group’s special lecture series for women in the international community.

Below is the transcript from the event.

(reference note – A an excerpt also appeared in: A Moment’s Peace – Newsletter AMP/1982-01 August 1982)

June 1982 Mrs. Margaret Y. Catley-Carlson, Deputy Executive Director (Operations, UNICEF:

I want to start by saying how impressed I am with the beauty of your choir and your choral rendition. It was truly lovely. I’ve had quite a morning, and I’m sure most of your mornings are as fractured as most of mine. We run from one meeting to another and receive telephone call after telephone call. To sit for a few minutes and let the true beauty of music wash over me, particularly when it is entwined with the theme of UNICEF, is a moment in my day which I shall certainly cherish, and I congratulate you all for that.

Thank you for inviting me. It is a particular honour to be invited by a group such as yours to deliver my thoughts. It is, however, a challenge. The very quality of this group, to me, makes the sharing of these thoughts more difficult. What does 33 one need to say about development and disarmament to a group dedicated to the renunciation of limitations and ignorance, and to peace in both the inner and outer world-world peace, world love, world union and world emancipation? Because of where we come from, we already share a number of the same perspectives. I think it is easier in some ways to face an audience of skeptics who think that development really is not worthwhile, that it is a waste of time and money and that it never works, or that disarmament is just an idle dream, and if we arm ourselves to the teeth, this is the best protection against our enemies. With these people, at least one can quote facts, test assumptions and challenge theses. But as I said, we are starting from the same place. In short, it is not necessary to tell you that disarmament and development are two of the great necessities of our time.

So I thought about – perhaps I meditated on what might establish a useful communion of minds as I stand on the platform before you, and as you take time out of your busy day to devote some mental energies to the great themes of disarmament and development. I have read something about your group, and I came up with three ideas that might lead to worthwhile reflection.

The first was the question of hope. I read in one of your publications that Sri Chinmoy reminded all of you, “Hope is power. … Inside hope there is power.” He went on to say, “There are many people who don’t hope. Either they don’t know how to hope, or they don’t want to hope.” It is much more fashionable to be cynical, but he said, “That is the wrong attitude. Hope is not delusion. Hope is not mental hallucination.”

Can we truly hope in development? I think that in development the grounds for hope are really quite clear. Consider these things : the world for the first time has the capacity, the knowledge, the resources and, in most places, the will to mount a decisive campaign against mass hunger, ill health and illiteracy. It is the first time we’ve really possessed these capacities. Consider the following: since World War 11 developing countries have doubled their average incomes and halved their rates of infant mortality – astonishing achievements! Life expectancy, in tPe same period, has increased from 42 years to 52 years – a monumental increase, and one that took those parts of the world which we normally refer to as developed many centuries to achieve, as opposed to the two decades taken by the world which we consider underdeveloped. Average literacy rates in the same time period moved from under 30 percent to over 50 percent – again in Europe an achievement of centuries rather than decades. Between 1955 and 1975 the peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America brought 150 million hectares of new land into production, more than the entire present cropland of the United States, Car..:!da, Japan and Western Europe combined. This is a monumental achievement. Partly because of this and partly because of improved techniques, only one-tenth as many people have died from famine in the third quarter of this century as in the last quarter of the last century.

I think, and here I join myself with Sri Chinmoy, that sometimes it is necessary to look at the beacons of hope, because the beacons of despair, particularly in the development field, are all too readily apparent.

Now it would be splendid to believe that because all of this is possible, because the will is being exercised in many places, and because this amount of progress has been realised, that accelerated development will also soon be realised. We who work at the United Nations and listen daily to its message, know that it is not this simple. Income projections show that we are moving towards greater numbers of absolute poor in the world. The gap within developing countries in income, benefits, health and nutrition also continues to widen. There are more people, and there are more absolutely poor people. The challenge is becoming greater, not less, even though the weapons to accomplish the task are more in hand than they have ever been. This is, if you wish, the great paradox of development.

Is there hope in regard to the question of disarmament? To my mind the grounds for hope are less clear. Yet at the same time we must attach hope to the new and growing wellspring of public sympathy, of public support and of public conviction that the time has indeed come to do something about the menace that hangs over our heads. There are welcome changes in the press treatment of disarmament issues and , indeed, in the composition of those groups which now challenge the assumption that more armaments are necessary. I think of the press reaction to these groups and issues a scant twelve years ago. I think of the fact that the protest movement about arms and armaments diminished and was not a voice of vigour over the last decade. I think now of last Saturday, which I spent – as I am sure many of you did – in Central Park giving the June 12th message to the world that something must be done to stop what is being considered more and more widely as a monumental threat to human existence. Whole states, whole cities, whole governments are declaring themselves in favour of cutting the knot. They are saying, if we can’t start at ground zero, let’s not get to ground zero, but let’s at least start the process. I find hope in these reflections.

Development and disarmament themes are usually linked by those who would compare the costs devoted to arms against the needs of development. I think it is right and necessary to do so. The resources, for example, that low income countries would need in order to meet the minimum needs of all by the year 2000 (and this is minimum needs: water, shelter, basic education, nutrition at the very minimal caloric levels) have been estimated at between 12 to 20 billion a year for the next 20 years in 1978 dollars. This is a vast sum of money, but no more than the world spends on arms every 15 days.

Put in another way closer to home, in terms of UNICEF, the world’s military expenditures every four hours are equivalent to UNICEF’s yearly budget. Every four hours the world spends in arms what we in UNICEF spend on a yearly basis to take on the staggering burden of the needs of the world’s children.

There are other important links, though, between disarmament and development which have certainly been brought vividly home to us in UNICEF during the last week, when our staff has been working around the clock to try to bring relief to the children and families of Lebanon. Whether a child is shivering from cold because of flight from the family home in the wake of armies, or because the family income cannot protect him, because his area has become deforested with the rise in the price of petroleum or because he is hungry and there is simply not enough food intake to warm his body, he is still a shivering child. Whether a child is maimed by a stray bullet or an explosion too close, or whether that child is one of the one-of-ten born with special needs that result in a handicap because of poverty or lack of knowledge of how to cope with special needs in his society, it is still a laming, a maiming, a blindness or an impairment that could have been prevented, that became a disability and needed not.

It really doesn’t matter much whether a child is taught to hate as part of the grinding-down process of poverty, or taught to hate as part of the hatred of one race for another being inculcated into a child at an early age. The result is still the same: a hatred that turns a child against his or another society, and against being a productive member of world society. The 17 million street children who turn to larceny, prostitution and eventually serious crimes live with a mentality fostered by watching a world of health, education and comfort which they will never have. These children are not much different from the children of 10 and 11 whom we see on the newscasts picking up guns and hurling hand grenades at enemies whom they also do not know.

One hundred million children go to sleep hungry at night because of poverty. They are joined by those whose hunger results from the war-destruction of fields, warehouses and distribution systems. I guess it makes no difference if you are one of the 200 million children from 6 to 11 years old who have no school, or just one of the hundreds of thousands whose school is destroyed or has to be used by the community for shelter because the houses have been destroyed. The result is the same: 38 • no school. And when you come right down to it, it probably doesn’t matter whether a child is one of the 40,000 who die every day from malnutrition, poverty, disease or neglect, or one of the few hundred that died in the last month when the world resorted to force in four places in the world. That is the second connection between development and disarmament – the effects of their lack are so startlingly the same.

The third connection is perhaps the most important of all, and it is probably the one I will have the most difficulty communicating, because it is in understanding this connection that I think solutions begin to emerge. Recourse to arms and lack of development both result from profound communication breakdowns. This is a coin with two faces. That children die, that people starve, that there is waste, that arms are picked up, that societies turn to guns to solve problems, these are the most profound and absolute breakdowns of communication in the human system. In terms of hope, both these represent the most profound intellectual challenge of our time. The techniques and the capacities may be simple, but how do we apply them? The answers are of staggering complexity.

Let me go into this for a moment. If you double food production, do you solve malnutrition? No. In Ireland, for example, in the last century, food exports actually rose-yes, food production increased during the Irish famine – and yet hundreds of people starved. The same thing happened in the great crisis of the Secherasse in Mali. Exports of cash crops from Mali to Europe rose during the Sahelian drought, while the people and the cattle of that region starved. Costa Rica doubled meat exports at the same time it had to reduce domestic 39 protein consumption. In the Congo and in Sierra Leone, food production has risen over the past few years, but malnutrition has increased rather than decreased. More food does not mean the end of malnutrition; more money does not mean development. More money can, in fact , increase malnutrition. When the family arrives at the state of income where it has enough money to stop breastfeeding and buy Coca Cola, it may do both. As a result, more money may actually be increasing malnutrition.

Money does not buy peace. Development does not buy peace. Until populations reach a certain level of development, there is neither the degree of nutrition, well-being and strength, nor the degree of education or knowledge, to actually revolt against the conditions that are causing the underdevelopment. When you add money, when you add development, you increase the chances that there will be less peace. These are staggeringly complex realities. More arms does not mean more peace; at the same time, more arms has meant, in some cases, the absence of war. There is no doubt that the fear of war has installed a balance of terror in some places.

To my mind it is in the acceptance of the complexity of these equations that cut across development, disarmament, money and peace-all the questions of human survival- that we begin to find their solutions. The main enemy is the quest for the immediate and simple remedy, because the questions and answers are of such complexity that the problems will not admit to simple remedies.

The fight against the total extinction of the human race is not the major challenge we face. Survival of at least part of the species is highly likely in all circumstances. It is highly unlikely that present and future generations will so devastate this planet (even though we have a great proclivity to do so) that each and every man, woman and child will perish. It is always possible, but it is improbable. The milin limits to human growth are not based on the fact that we’re likely to inculcate a form of terror in ourselves by the nuclear challenge, or on the fact that we do not have the capacity to cope with development. They are not based on rigid facts of nature, but on current social and political institutions, on the relations among states and the relations of human beings to each other. I don’t think our future lies in doom by the depletion of the environmental resources , nor do I think that it lies in the automatic salvation of technology. We may run up against some resource limits. We may even, if we are not very careful, bring terrible damage to the planet, but the limits which constrain our future are political and social, rather than physical. Human survival may, in fact, require more than we are prepared to give of our daily lives. The major issue we face is the survival of beings as persons who are fit to live with, and of the earth as a place which is fit for persons to live in.

The questions themselves are not simple. I think groups like yours are doing a great service and have a great place to fill in exploring the nature of the institutions, the nature of the problems and the nature of the solutions. To me the first step lies in accepting the complexity of the problems. At the same time, we must solve these problems along principles which are simple, that is, that we have an obligation to our fellow man, that it is not necessary, or at best should be a very last resort, to 41 inflict force on our fellow man, and that force ought not to be used to bring a communality of view on an issue. To me, the main foundation upon which we find the solution is the acceptance of the fact that each one of us has a responsibility within that complexity, and the acceptance of the challenge which you have taken on, which is that both inner and outer peace are well worth the effort. Thank you .

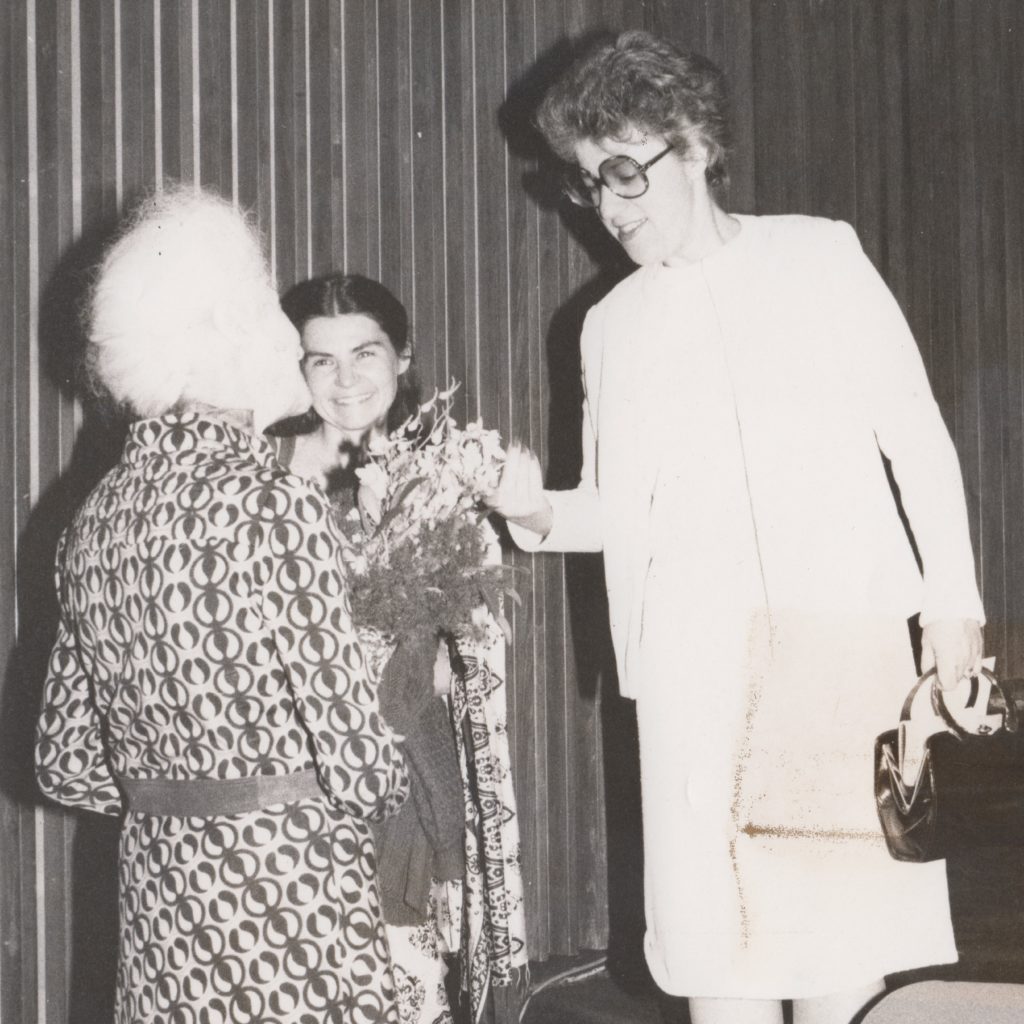

1982-06-jun-21-disarmament-catley-carlson-unicef-asg-mrs-rossides-presents-flowers-1-scaled.jpg 795 kb

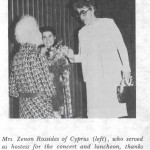

Mrs. Zenon Rossides of Cyprus (left), who served as hostess for the concert and luncheon, thanks Mrs. Catley-Carlson for her illumining talk.

This transcript was issued as part of : Meditation at UN – Vo 10, No 05-06; 27 May – Jun 1982, Bulletin

Downloaed PDF: scpmaun-1982-05-06-27-pp-34-44.pdf

Click on image below for larger or different resolution photo – Image:

- 1982-06-jun-21-disarmament-catley-carlson-unicef-asg-speaks-crop-scaled.jpg -779 KB

- 1982-06-jun-21-disarmament-catley-carlson-unicef-asg-mrs-rossides-presents-flowers-scaled.jpg – 795 KB