DEVOTIONAL SOUTH INDIAN “Carnatic” MUSIC – Narasimhan – Playbill reproduction, 1978 May

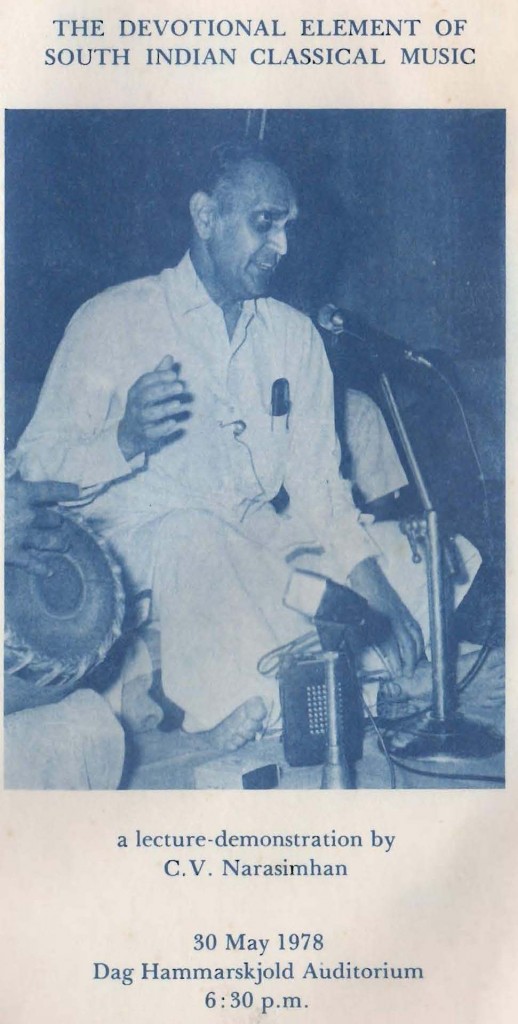

Filed under Music and Songs | Tributes and Expressions of appreciationTHE DEVOTIONAL ELEMENT OF SOUTH INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC

a lecture-demonstration by C.V. Narasimhan

30 May 1978 – Dag Hammarskjold Auditorium

6: 30 p.m.

Mr. C. V. Narasimhan. Under-Secretary-General (or the United Nations Office of Inter-Agency

Affairs and Co-ordination, offers a lecture demonstration on the devotional element of South Indian Classical Music, sponsored by the Meditation Group.

Reprinted here is an illumining article by Mr. Narasimhan which appeared in Stagebill, the

publication of Carnegie Hall, in October 1977.

Reference Note:

See also

- A summary of event : Musical Lecture- SUMMARY – Demonstration by C. V. Narasimhan which also appeared in 1978 Devoted Report to the Secretary General.

- ffor fuller report and more photos see – Musical Lecture – ARTICLE- Demonstration by C. V. Narasimhan which was published in the June 1978 Periodic Bulletin: “Meditation at the United Nations” pp 17 -30.

Introduction to Carnatic Music

by C. V. Narasimhan

The music of south India, like many traditional arts, has developed over several centuries and is today a highly sophisticated and complex system. To understand this music one has to listen to it , not only with an open mind, but also with open ears. In this short piece, an attempt will be made lo explain some of the main aspects of this music, which is called “Carnatic” music.

The first , and most essential, difference between western music and Carnatic music is that the latter does not use harmony. hut only melody. It is true that a curtain tone’ is provided as a backdrop by the sruthi, or drone , usually in the form of either the tambura or the harmonium. But the sruthi, or the pitch of the drone, is the same for all the musicians participating in a concert.

The second important difference is that Carnatic music is based on a constant pitch – in other words, whatever melody is sung, the tonic remains the same . For example, starting with different notes on the piano and p laying the consecutive notes making up an octave , you could have the equivalent of different modes (ragas). But in the Carnatic system these tonal combinations will all be accommodated within the octave starting from one constant tonic.

The concept of the raga, or mode, is basic to the understanding of Indian music (both north and south). A raga is a fixed group of tones, including Semi-tones and micro-tones, in their ascending and descending order, ranging usually from the fifth below the tonic to the fifth above the octave giving a range of some two octaves. It is important to remember that the structure of the raga is ordinarily rigid; no tone, other than the authorized combination, can be introduced into it. One would think that this would make the raga system somewhat restrictive, but the opposite is true. A raga may use a scale of 5, 6 or 7 tones, and it may also take a different aspect (basically sharp or flat) of the same tone in the ascending or descending order. Further, a raga may take only 5 tones in the ascending order and use 5, 6 or all 7 tones in the descending order , or vice-versa, with all kinds of permutations and combinations of this nature.

A further subtle feature is the use of the vakra, or crooked, ascent or descent, where the raga may ascend to a certain point and then turn back on itself and descend one or two points before resuming its ascent. The same technique can be used in the descent also.

The whole raga system has been systematized on a scientific basis and classified into 72 parent (melaharta) ragas. A parent raga should take all the seven notes of the gamut. Taking into account, however, the possibilities mentioned earlier and also the innumerable possibilities arising out of the use’ of the vakra , the permutations and combinations of the derived (janya) ragas are astronomical in scope. However, it is true to say that, by and large , less than half of the parent ragas are in common use, together with two or three hundred other derived (janya) ragas.

Another aspect of the rendering of tones in south Indian music which makes it so different from western music is the use of the gamaka, or oscillation. The result is that apart from the tonic and the fifth, the other tones in a raga are in a constant state of flux, approximating closely to the tone above or the tone below and often oscillating between the two.

Another important aspect of south Indian music is the use of the tala or rhythmic pattern. The rhythms of Carnatic music are fairly easy to understand insofar as they approximate to multiples of two or three beats. However, there are other talas in Carnatic music which use, for example, combinations of 5 and 7 beats, and these may be a little strange to begin with, but they become quite easy to understand after a little practice in keeping- time. It is very common, however, for the opening syllabic to start, not with the beat itself, but a fraction of a beat later (say one quarter, one half, three-quarters, etc.) and sometimes even a fraction ahead of the beat.

I now come to the songs. The greatest achievement of Carnatic music is the development of the song form known as the kriti. The kriti usually consists of an introduction (called pallayi), the middle part, where usually the music rises above the octave (called anupallavi), and a last part (called charanam) , the first half consisting of music usually set in the lower half of the gamut, and the second half usually a repetition of the middle part (anupallavi). For example, the first part may consist of just one line – the second part of two lines and the last part of four lines, the last two lines of which would be sung practically in the same way as the middle part. Each line is sung (or “swung”) a number of times, but introducing variations as the line is repeated or swung, These variations (called sangathis) are designed to illustrate either the beauty of the raga or to bring out the particular meaning of the line. In many cases one line may be picked up for detailed exposition, both in terms of the raga and tala: this is called neraval. You will also hear the swaras or solfa syllables being sung to illustrate the raga and its special. characteristics as pa rt of the song itself (in which case it is called chittaswara) or as a matter of improvisation (in which case it is called kalpanaswara).

Some of the songs are preceded by brief or, as the occasion demands, lengthy explanations of the raga or the mode, and this is called the alapana. This singing without words and without a rhythmic pattern is one of the most important elements in the delineation and development of the full beauty of a raga. It is made up of a number of phrases and also some coloratura passages of great beauty and appeal to the ear. The alapana is always an improvisation.

Another important difference between the western and Carnatic systems is the scope offered by the Carnatic system for the inventiveness, improvisation and imagination of the artist. For example , while the kriti itself and its sangathis may be somewhat rigidly structured, there is tremendous scope for originality in the alapana, neraval amd kalpana swara singing.

·As for the accompaniments, the tambura, or drone, provides the tonic and, as said earlier, the musical backdrop to the whole program. It is tuned to the tonic, its octave and the fifth, and is strummed constantly to provide this curtain of sound . Also , by the adjustment of a piece of silk thread which, in effect, isolates the string from the bridge over which it is tightly stretched, the sound produced continues to murmur, so to speak, for an almost indefinite period, giving it a reverberatory quality.

The violin was adapted to Carnatic music only during the last century, and was popularized by a great musician named Tirukkodikkaval Krishna Iyer. Since then it has almost replaced the veena as the most important instrument of Carnatic music, particularly as an accompaniment. Unlike the veena, the gamut is accommodated physically within a much shorter range on the violin’s fingerboard. It is also possible to play very fast coloratura passages on the violin more easily than on the veena. It should be noted that the violin is tuned differently from the way in which it is tuned in classical western music.

One of the glories of Carnayic music is the percussion instrument, known as the mridangam. One side of the mridangam (usually the side visible to the audience) is finely tunedto the same tonic as the tambura. By striking different parts of the tuned side of the mridangam, the percussionist can also produce a variety of tones approximating closely to the tones of the raga itself. The other side of the mridangam, which is not visible to the audience, is not tuned and provides a bass counterpoint to the tuned side.

There are two other aspects of Carnatic music, especially concert music, to which I would like to refer. One is that the music is homophonic, meaning thereby that the same melody is sung or played by all the musicians at the same pitch. They do not necessarily sing or play in unison, and they may be a little out of phase. Also, when the principal artist is engaged in neraval or kalpana swara singing. a little rivalry develops between the principal artist and the accompanying artists. both on the violin and on the percussion, and this becomes highly attractive to the audience. The other aspect of Carnatic music, which is sometimes disturbing to western listeners, is audience participation. As the music proceeds. a ripple of appreciation may emanate from members of the audience. many of whom will also keep time, sometimes not too correctly. On one occasion when I was indulging in this practice of keeping time at a concert before an international audience, I was sharply reprimanded by a European lady sitting behind me and asked to keep quiet.

It is also important to remember that, while a fair amount of secular music, particularly film music, has developed during recent years, the great treasures of Carnatic music composed by our greatest composers are basically devotional in character. The songs usually contain an appeal to the Lord or the Divine Mother for compassion, a wish to be in constant communion with them or a description of their glorious feats, as described in Ill(‘ sacred literature (the Puranas) of Hinduism. It wlll dd indeed be true to say that the music is designed not so much to please the ear as to touch the heart.

UNITED NATIONS:

the Heart-Home

of the World-Body

The Meditation Group is an association of United Nations delegates) staff, NGO representatives and accredit ed press correspondents.

This information is presented as a service and does not necessarily represent the official views of Ihe United Nations or its Agencies.

See also

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – Details Below – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Download

- PDF-OCR text format:

- Word doc of Text format:

Page images ( click on image below to enlarge)

- bu-scpmaun-1978-05-30-supplemn-u-s-g-narasimhan-music_crp