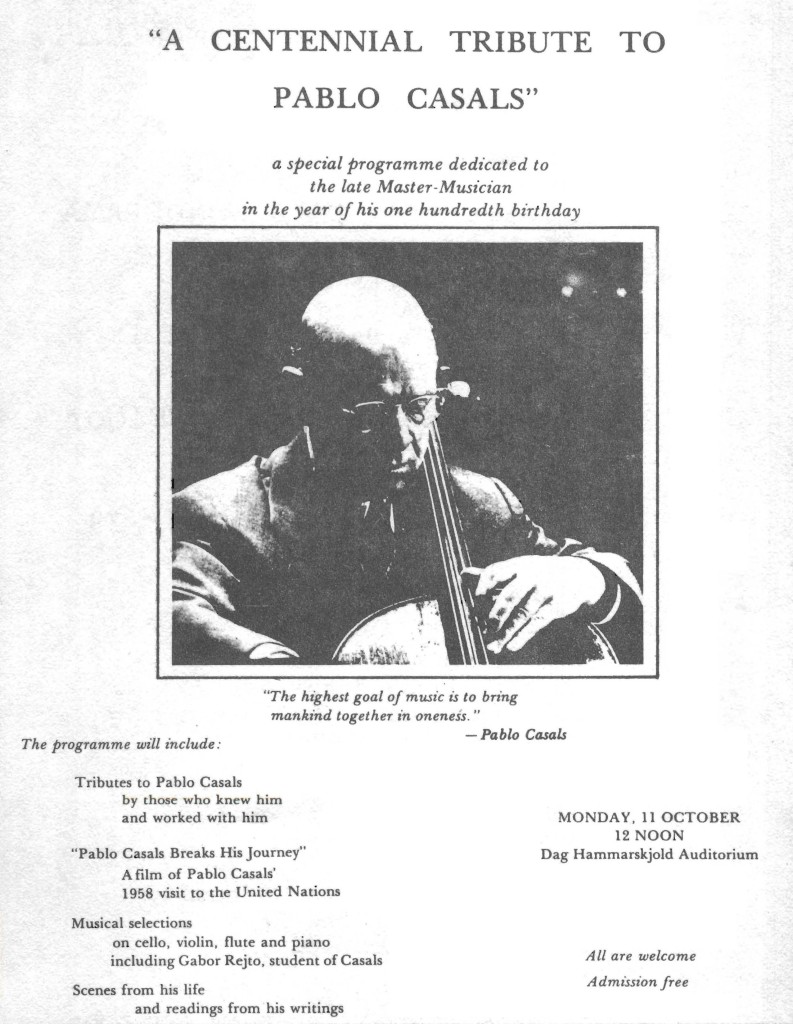

Centennial tribute to Pablo Casals at UN – 1976 Oct 11

Filed under 2 or more | Music and Songs | Tributes and Expressions of appreciationIn 1976, the centennial of Pablo Casals’ birth, United Nations staff members and delegates joined together in a programme sponsored by Sri Chinmoy: The Peace Meditation at the United Nations to pay tribute to the great cellist.

The programme took place in New York on 11 October. The Spanish Ambassador to the United Nations, Don Jaime de Piniés, paid homage to Pablo Casals as “a symbol of the power of the spirit.”

Other staff members recalled the beautiful “Hymn to the United Nations” that Pablo Casals composed in 1971 at the request of U Thant. The Secretary-General awarded him a United Nations Peace Medal for this work.

Sri Chinmoy concluded the programme by reading extracts from his meeting with Pablo Casals in which the Maestro spoke of the child as a miracle of God.

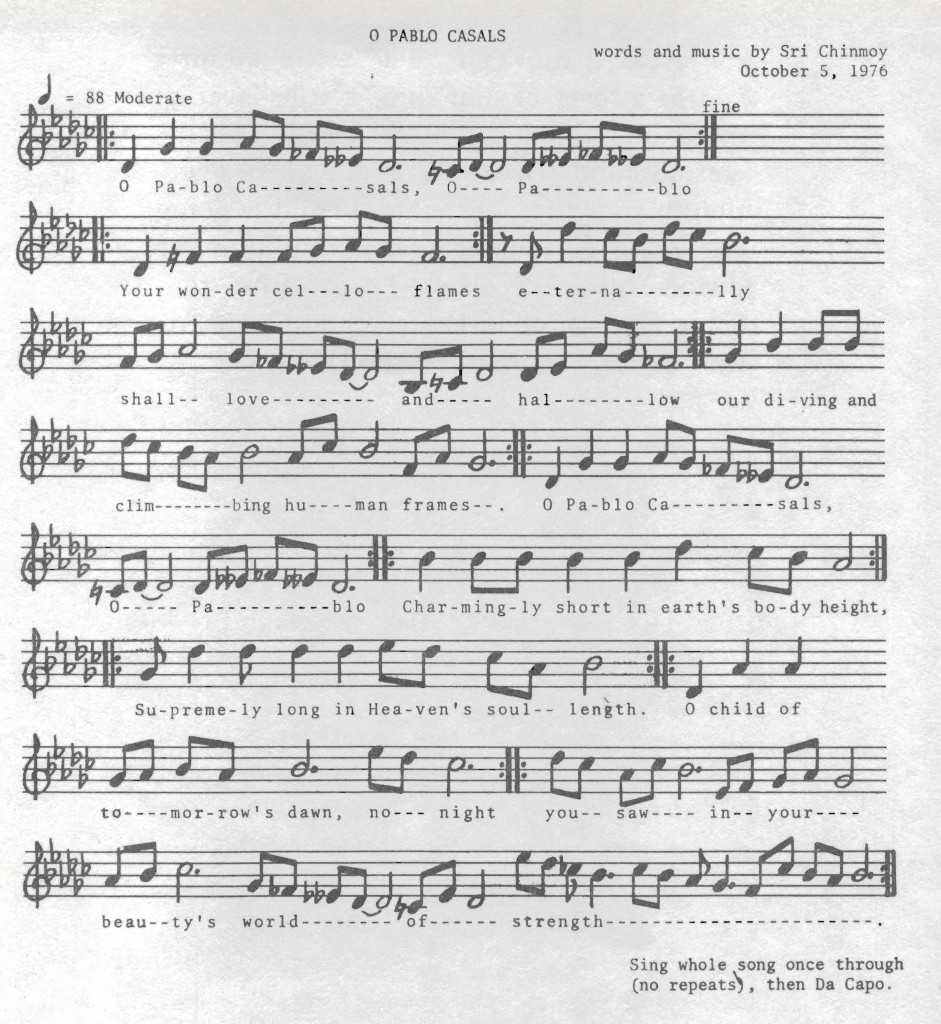

O Pablo Cassals

O Pablo Casals, O Pablo,

Your wonder-cello-flames

Eternally shall love and hallow

Our diving and climbing human frames.

Charmingly short in earth’s body-height,

Supremely long in Heaven’s soul-length,

O child of tomorrow’s dawn, no night

You saw in your beauty’s world of strength.

The above summary of “Centennial tribute to Pablo Casals” was included in “ Four Summit-Height-Melodies”, by Sri Chinmoy, Agni Press, 1995

Below are fuller extracts of the event which appeared in “Meditation at the United Nations” of Oct 1976 page 25 – 42

CENTENNIAL TRIBUTE TO PABLO CASALS

(to be spell checked and formatted)

In tribute to Pablo Casals on the centennial of the great cellist ‘s birth, delegates and U. N. staff joined together in a programme sponsored by the Peace Meditation Group at the UN on 11 October in the Dag Hammarskjold Auditorium.

- Spanish Ambassador Don Jaime de Piniés offered his respects and

- Sri Chinmoy, who had met with the Maestro shortly before his death, read out an excerpt from their soulful conversation.

- Personal reminiscences were offered by Ms. Sylvia Fuhrman of the United Nations School, who ‘had worked with Pablo Casals and offered concerts for the benefit of the School, and

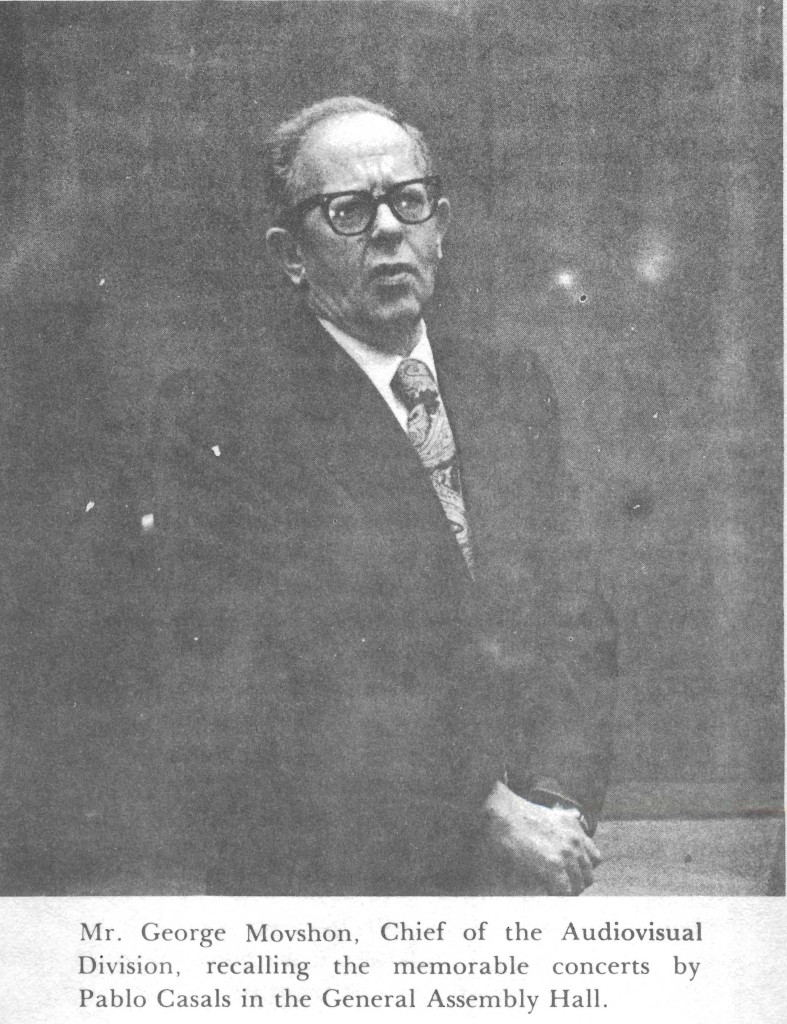

- Mr. George Movshon, Chief of the Audiovisual Division of the United Nations.

Ambassador de Piniés:

It is especially pleasing and an honour for me to participate in this homage to Pablo Casals on the occasion of his centennial. We are here to pay a deserved and justified tribute to him since if there has been, during the three first decades of the United Nations, a person who has honoured and who has fulfilled during his lifetime the ideals of this Organisation, this person has, without doubt, been that universal Spaniard, that universal Catalan, whose memory today brings us here together.

H.E. Don Jaime de Piniés, Ambassador from Spain, offers his formal respects in a eulogy to Pablo Casals.

H.E. Don Jaime de Piniés, Ambassador from Spain, offers his formal respects in a eulogy to Pablo Casals.

The first steps toward autistic glory are not always easy. The young Casals, a modest man from the provinces, solely armed with his father’s fiddle bow and with his background of aesthetic ideals, needed and obtained official support to begin his career and he never forgot the protection and encouragement given him by Queen Maria Cristina, opening his way, first in his country, and also facilitating. during me century’s close, his brilliant appearance in Europe’s musical world.

Casals was not only a genial instrumentalist and the founder of the violin cello’s modern school of cello playing, but also one of the great men of chamber music and the Maestro of various generations of violin cellists. But these artistic merits, which secured for him an outstanding place in contemporary art, were also indissolubly linked to his dimension as a humanist which has made him into a symbol and a legend. His life, as with many other Spaniards of his generation and the following ones, was not free from the troubles and the sorrow derived from extremely violent social and political convulsions. During the many years of his absence from Spain, he always maintained his loyalty to her, since he felt his love for Catalonia, his love for Spain and his love for mankind as a triple dimension of a sole feeling of human solidarity.

His visits to the United Nations and his performances here-some of which 1 vividly remember were testimonies of his profound faith in the ideals 27 of peace, human rights and international cooperation which inspired our Charter.

The measure of genius is often found in the perseverance and in the depth with which it knows how to search, in the realm of moral values, for the more authentic roots of artistic inspiration. This was the glory which was Michaelangelo, Shakespeare, Beethoven and Goya. And also Pablo Casals, who knew how to convert his art and the irradiation of his personality into a permanent tribute to the humanistic values he considered paramount, without ever falling back on the artist’s supreme sacrifice, that of renouncing the public communication of his artistic message when he feels that this silence is demanded in the service of his moral testimony.

Casals is a source of inspiration for those who, professing the very same ideals of peace, solidarity and universal cooperation, sometimes feel discouraged before the difficulties which life and the heritage of ancient prejudices place in the path of their fulfilment. It is just, therefore, that the United Nations offer, in turn, a tribute to his memory and that it be recalled in this hour of meditation. Casals is a symbol of the power of the spirit, and we indeed need, in these difficult hours through which the world lives, the light and the example of figures like these so that we may continue our daily work in this Organisation with renewed energy and the devotion which the world and our own countries have the right to expect.

Ms. Sylvia Fuhrman,

United Nations International School

Ms. Fuhrman: I was a close friend of Pablo Casals, but our relationship was not a formal one. I was involved with him in his United Nations activities, particularly in his composition, “Hymn to thé United Nations.” You might be interested in some of the background of that.

When U Thant asked Don Pablo to write a hymn to the United Nations, he said fine, he would be most honoured to do so. The Secretary-General suggested that he use as the text of his composition the preamble of the United Nations Charter. When Casals read the preamble he was most impressed and he said, “Of course, this is precisely what 1 want to write my music to. But how can 1 write music to institutions, resolutions, constitutions. We must have the same spirit in more poetic language.” And so we had to make the decision of the poet to rewrite the preamble to the Charter and paraphrase it in such a way that Casals could write his music.

And, of course, W.H. Auden was the foremost writer in the English language, and his poetry was certainly accepted as the finest of any living poet. Although Casals wrote his music in a romantic tradition while Auden’s poetry was very modern, the two men were able to collaborate together in totally different styles and yet make beautiful music together, as those of you who have heard the hymn know.

Ms. Sylvia Fuhrman of UNIS relating personal anecdotes from Pablo Casals’ visits to New York when the Maestro stayed at her home.

Ms. Sylvia Fuhrman of UNIS relating personal anecdotes from Pablo Casals’ visits to New York when the Maestro stayed at her home.

It was unfortunate that Auden and Casals never actually met each other. I had the happy chore of being the courier between them. Somehow, when one of the gentlemen was in New York, the other was away. When Casals was in Europe, Auden was in the States, and vice versa. And it was asad thing to both of them that they never met. Unfortunately they both died within a short time of each other. Casals wrote many compositions. He was a composer. This part of his musical history is not well known. He wrote his first composition when he was seven years old. And he wrote some beautiful, sacred music for the Abbey of Montserrat in Spain, where in about three weeks they are going to erect and dedicate a large monument to Casals. In the base of the monument will be a replica of the United Nations Peace Medal that was awarded to him by U Thant in 1971 for his composition “Hymn to the U.N.”

It is his own country, the country that he loved so much, that now recognises him in this way for his centennial. If 1 might take a minute to be personal, I would just like to tell the story of the end of the day when Don Pablo gave his last concert here at the United Nations, when the hymn was performed. It was a very full day, and afterwards that evening there was a large party that went on until about one in the morning. Maestro loved parties, and he was always very animated and very excited. When the party was over and everyone had gone home, we were readying ourselves for bed and had put on our nightclothes. He became very sentimental as he often did and said it was such a beautiful day that he wanted to say thank you, but how could he say thank you? There was only one way he really knew how, and that was to play for us. There we were, four of us in our nightclothes, and he took out his cello and played for more than an hour. He played the Bach suites which, as many of you must know, were his favorite compositions. And this was typical of his lifestyle: one of great sentiment and great love.

I have the happy chore this day to bring the special greetings of Martita Casals Istomin, his widow. She tried actually to be here today, but she’s involved in another centennial ceremony in Mexico, and was unable to come. But she said to please send her very special greetings. Her heart is always with the U. N. as the Maestro’s was.

Mr. George Movshon, Chief of the Audiovisual Division of the U. N.

Mr. Movshon: I have a certain interest in music. I write about it as a hobby and, many years ago, when they found in the Secretariat that I did have this enthusiasm,’ I was brought into the administration of the two concerts that happened regularly each year in the Concert Hall of the United Nations: the U.N. Day concert and the Human Rights Day concert.

Mr. George Movshon, Chief of the Audiovisual Division , recalling the memorable concerts by Pablo Casals in the General Assembly Hall.

This is rather like the army man, the sergeant, who asks for volunteers with knowledge of music, and when two step out he tells them to push the piano. But I enjoy pushing the piano two times a year. It some times runs into incredible complexities, but one result of this talent for pushing the piano is that it brought me on three occasions into some contact with Don Pablo. He came here first in 1958 and you will see, in a little while, the movie that was made on that occasion.

In 1963 he came back with his Cantata El Pessebre (“The Manger”) which involved a large orchestra and choral soloist. And in 1971 he came largely through the instrumentality of Mrs. Fuhrman to give us an afternoon of music which all of us who were in the hall or who saw it on T .V. will not easily forget.

If you study the history of music, you find that some composers and some artists and some singers have relatively brief careers. Mozart and Schubert never made it to their fortieth year. We think of people like Giuseppe Verdi and Arturo Toscanini to be very senior, mature figures in history, and they were in their eighties.

When Don Pablo conducted, spoke, played the cello, went to two receptions and drove here frorn Mrs. Fuhrman’s home and back on that 24th of October, 1971 , he was 95 . I’ve looked in the reference books to see if there was any artist that was fruitfully at work or before the public in his 95th year, and I haven’t found anyone. It was a phenomenon. It was some internal dynamo that kept him going all these years right to the end.

When you consider this, I was speaking to someone who remembered Queen Victoria. And it was not some childhood memory. He was an adult, a young adult, when he went with his mother and little brother, who was at that time a babe in arms, to the Palace to play a Royal Command private concert for the Queen of England. This was not something that was to him a dim childhood memory. It was something that happened when he was a fully mature young artist. He mentions an incident about his mother, who was a simple Catalonian country woman, very unsophisticated by the values of the world in which Casals was soon to move and certainly by the values of the royal household of England. He remembers during the recital that his mother was holding the baby in her arms. Suddenly the baby started to cry and all the people looked around. With the absolute natural simplicity of a mother, Mrs. Casals senior gave the baby her breast to suck. This is something I guess they remembered in Queen Victoria’s palace, Casals responded to me many years afterwards on an afternoon that was made possible by Mrs. Fuhrman. I remember I drove out to her home and had the pleasure of spending several hours in her garden, just talking to Don Pablo and asking him 35 questions about all sorts 0f people, long dead, that he knew in his youth.

I said, “Maestro, did you ever think that Gustav Mahler would achieve the popularity that he has today, especially with young people?” He nodded and grunted a couple of times and said, “Well, you know Gustav Mahler was always a talented boy.” There is one story ; it is a pocketful. I tell you right off that it didn’t happen, but it could have happened. A few years before his death he was rehearsing in Puerto Rico a performance of the Brahms “Serenade for Orchestra .” At one point he stopped the musicians and said, “The third bar, please don’t play the note that is printed, B natural, but make it a B flat.” One of the musicians afterwards protested. He said, “Maestro, this is not Monte Verdi, this is the printed music of Johannes Brahms, and you can’t just re-edit it in a rehearsal like this.” And Casals is reported to have answered , “No, no, Sasha , Brahms always told me he liked it better this way.”

Anyway, the day before the 24th of October , we had a hair-raising rehearsal. There was a problem with the lights in the General Assembly Hall, the lights which we needed for T .V.-which was indispensable for the sharing of this event with people all around the world and through the years. The lights proved an almost impossible obstacle for Don Pablo, who couldn’t stand them in his eyes and who got hot. At one moment we thought he had collapsed on the podium, and a dozen people gathered around him and we helped him out of the strong light. He sat at the side of the stage, with his homburg hat on, at the piano. And I thought, “My God, it’s something. I shall go down in history as the man who brought down Pablo Casals.” I thought for a moment. He said, “It’s better, Mr. Movshon. It is better. I will be soon all right. But you have to remember,” he said, “that I am a very old man.” And I did indeed remember that.

But that very old man, the next morning, arose at seven. He was staying at Mrs. Fuhrman’s house, and very early on there was an argument as to whether he should make a big speech or only a small speech from the concert platform. It was decided that he would make a small speech. He then did something which he never omitted doing. He played Bach on the cello for some time. Towards the middle of the day, he was driven to the U. N. and then, in the presence of thousands of people and hundreds of musicians and dozens of T. V. technicians and assistants like me, this man conducted his hymn twice, conducted two Bach concertos – one for two violins and one for three pianos-made two speeches and embraced the Secretary-General. Do you remember that? When U Thant appeared to give the Peace medal, he looked up and put both arms around the Secretary-General. These two men clutched each other for what seemed a very long time. And Mr. Thant conceded to me afterwards that he hadn’t been embraced so tenderly and compassionately since Duke Ellington.

He attended a long reception upstairs. He made two speeches and he played the cello. He then went upstairs to the second floor and attended the Secretary-General’s reception, where he spoke to perhaps a hundred people. He then was taken to Mrs. Fuhrman’s house where he permitted himself a small rest. But there was a dinner party with singing that went on late into the evening. I was knocked out by 9: 30 and went home. But he went on and, as you heard, in his nightclothes played a little farewell on the cello to assure his coming safely through the night.

I haven’t spoken of the deep things of Pablo Casals, but my comrades on the platform have done that very nobly. I remember him as quite remarkable, with a unique place in the history of music and the music profession. I was very aware that he, among the other things, loved Catalonia and liberty. The musical profession, his colleagues, the brotherhood of music, was something that he had enormous regard for, something that moved him very deeply. And the notes themselves, the fiber and the fabric of music, was something that he took with him. I am sure that when they have a little chamber music up there, that that same fibre, that same feeling, is there as it was here on earth in everything that he did and everything that he thought. Thank you very mucho.

Sri Chinmoy : I would like to read from a soulful conversation I was most fortunate to have with the Maestro on 5 October 1972 in his home in Puerto Rico.

“Don Pablo: … The child must know that he is a miracle, a miracle, that since the beginning of the world there hasn’t been and until the end of the world there will not be another child like him. He is a unique thing, a unique thing, from the beginning until the end of the world. Now that child acquires a responsibility: “Yes, it is true, I am a miracle. I am a miracle like a tree is a miracle, like a flower is a miracle. Now, if 1 am a miracle, can I do a bad thing? I can’t, because I am a miracle, I am a miracle.

God, Nature. I call God, Nature or Nature, God. And then comes the other thought: “I am a miracle that God or Nature has done. Could I kill? Could I kill someone? No, I can’t. Or another human being who is a child like me, can he kill me?” I think that this theory can help to bring forth another way of thinking in the world. The world of today is bad; it is a bad world. And it is because they don’t talk to the children in the way that the children need.

Sri Chinmoy: I am so grateful to hear this because my philosophy is also the same. We have to feel that we are all God’s children It is only a child that makes progress and evolves.

Don Pablo: How can they make progress if the child doesn’t know what he is? His father and mother don’t know this. In the school the child doesn’t learn this. And this is what produces the humanity, the bad humanity, we have. This is my idea: the child must know from childhood. Sri Chinmoy: The child must learn from the parents . The parents have to feel also that theyhave the supreme responsibility. A child is the flower of God, a child is the instrument of God, the representative of God. The parents have to feel this. Don Pablo : But they don’t.

Sri Chinmoy: That is why the problem starts. If they feel that the child is representing God, then all the time the parents will teach this to their children.

Don Pablo: That is why 1 say that the children must know what they are, the miracle that they are, as soon as they understand the sense of the word. This is my idea.

Sri Chinmoy: This miracle means that the child represents God on earth. He is the chosen instrument of God. See, we admire you, the world admires you as a musician, the greatest musician. The world admires you as a lover of mankind, a true lover of mankind. Again, the world sees in you the eternal child. Greatness is not an obstruction in your life. The eternal child is going on, going on making and manifesting the divine Music, the divine Truth within you. So it is your child-heart, childlike heart, that is ready to manifest the Divinity.

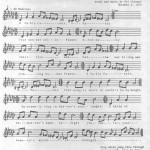

O PABLO CASALS words and music by Sri Chinmoy.

Download Report in PDF format: 1976-10-oct-11-pablo-casals-trib-bu-scpmaun-1976-10-27-pp25-42-opt

SEE Also: Don Pablo Casals and Sri Chinmoy 1972 Oct 6

Click on image below for larger or different resolution Photo – Image;

Gallery 2:

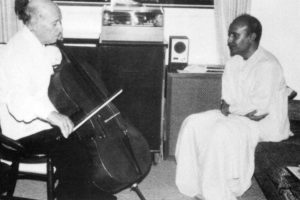

Some photos from Oct 1972 meeting

- Don Pablo plays a beautiful piece of music on the cello

- Sri Chinmoy meditates with Pablo Casals

- With-tears-flowing-from-his-eyes-Pablo-Casals-embraces-Sri-Chinmoy